March 23, 2024 by Zappy_snapps

What's the Difference Between Organic and Chemical Fertilizers?

When we buy fertilizers, they generally have NPK listed on the front, which gives the concentration of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium in the fertilizer. Organic fertilizers typically are sourced from plant or animal sources, while non-organic or chemical fertilizers are specific elements that we’ve determined plants need and may have been synthesized in a lab or mined from the earth. Why might you favor one type of fertilizer over the other? It comes down to nutrient availability, which is a double edged sword. To understand why, we need to know a bit about mycorrhizal fungi.

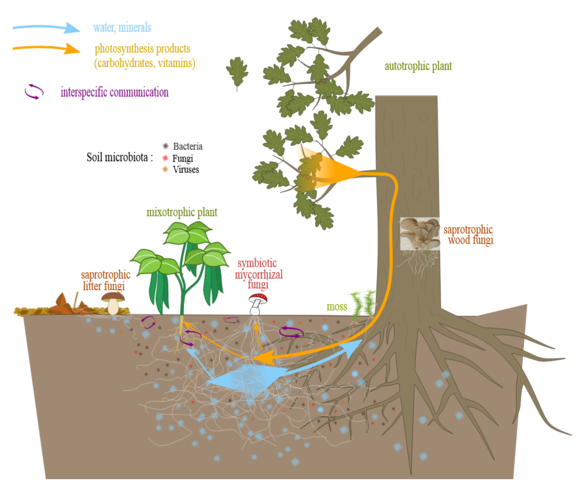

Plants need nitrogen and other minerals, and when growing without excessive fertilizers, they form symbiotic relationships with ecto- and endomycorrhizal fungi, which have vast mycorrhizal networks with incredible surface area. This allows the fungi to much more efficiently absorb minerals and water from the soil, which they exchange for plants’ root exudates, which have sugars that the plants have fixed through photosynthesis. Plants with these symbiotic fungi are more resilient to disease and drought, and grow better. The mycorrhizal fungi can also reduce plant’s uptake of heavy metals, and can prevent nutrient rich runoff.

When nitrogen, potassium, and especially phosphorus are too available, plants kick out their symbiotic fungi because they no longer need them to get these nutrients. However, this has a down side: symbiotic fungi protect against pathogenic fungi, so now those plants are more vulnerable to fungal infections. They also can no longer take up water as easily, along with other micronutrients that may or may not be in the fertilizer.

However, you may have noticed that I didn’t specify chemical fertilizers in the above paragraph, and that is because you can see the same effect in some organic fertilizers, like manure, rock phosphate, bone meal, etc. So it’s not JUST chemical fertilizers that can negatively impact fungi and their symbiotic relationship with plants – it’s any fertilizer that is too rich and too available. If our goal is to support mycorrhizal networks, ideally we would add just enough fertility and in a form that is more available to fungi than plants, thus encouraging those symbiotic relationships.

However, that does not mean that chemical or readily available fertilizers don’t have their place. If I’m growing something in a pot and it’s going to be in a pot its whole life, I’ll often use some kind of fertilizer that I wouldn’t use in my garden. Chemical or quick release fertilizers are great for when you’ve spotted a nutrient deficiency and want a quick turn around for your plants. I usually use some very rich sources of fertility for my cucurbits and raspberries, but learning this has made me rethink this practice.

I think an apt analogy is a box of strawberries and a soda. The box of strawberries has sugar, but it also has more micronutrients and will feed the kind of symbiotic bacteria we want in our gut in the long term. Meanwhile, the soda has a lot of sugar which will rapidly increase our blood sugar and feed the kind of bacteria that aren’t as beneficial. However, if your blood sugar is crashing and you need to bring it up, the soda is the better choice. Each has their place, and it’s best to analyze your situation and determine which is the better choice.

If you want to read more, here are some sources:

-

A Gardener’s Primer to Mycorrhizae: Understanding How They Work and Learning How To Protect Them (Home Garden Series) by Linda Chalker-Scott, available for free from Washington State University.

-

The Complete Guide to Restoring Your Soil by Dale Strickler – very in depth and a great book to read if you want to know more about soil.

This is a very complex topic and our understanding is expanding rapidly. I could not possibly cover everything there is to know about this in a single post, but I do think this is at least a good taste.

Some of the links in this post may earn Garden Revival a commission. Thank you for shopping through our links.